The Fall of Two Cities

April 1975, two capital cities, little over 200 kilometres apart fell to different communist armies within weeks of each other. In the chaos that preceded in both, hundreds of thousands had already fled from both Cambodia and Vietnam.

Between 1975 and 1982, it is believed that more than a million people left the two countries as refugees, often packed into small, unseaworthy boats. Many managed to reach neighbouring countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines, with countless of those less fortunate perishing at sea.

Destinations

Malaysia was just one destination for these ‘Indochinese’ refugees. However, like many countries in the region, the Malaysian government were not willing to accept them. The refugees were placed in camps before processing and resettlement in a third country under the policy of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

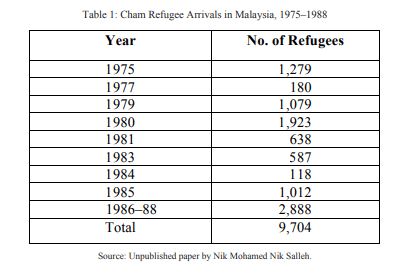

In Malaysia, it was estimated that more than 250,000 Indochinese refugees made their way through numerous transit points in the country before being resettled elsewhere. Due to fears including those of racial imbalance and security, especially over ethnic Chinese, the Malaysian government of the time refused to let the refugees settle in the country. However, a notable exception was made for 9,704 Muslims or practitioners of the Islamic faith, ethnically known as Chams or Islam Kemboja (Islamic Khmer).

The Refugee Crisis

Malaysia had been a staunch ally of the Saigon regime in Vietnam and the governments of Sihanouk in Cambodia, and later Lon Nol, following the coup of 1970. The nation had fought a long battle with a communist insurgency, known as ‘The Emergency’, which officially ran from 1948-1960, but was still simmering in the mid 1970’s, with bombings and political assassinations still commonplace.

When the first of the Indochinese refugees began landing on the shores of the Malay peninsula in April 1975, they were treated with sympathy. However, as their numbers swelled and showed no sign of slowing, public opinion began to shift, and the immigrants were seen as a possible threat to national security. In 1977 the refugees were reclassified as illegal immigrants under the Immigration Act, and banned from leaving detention camps.

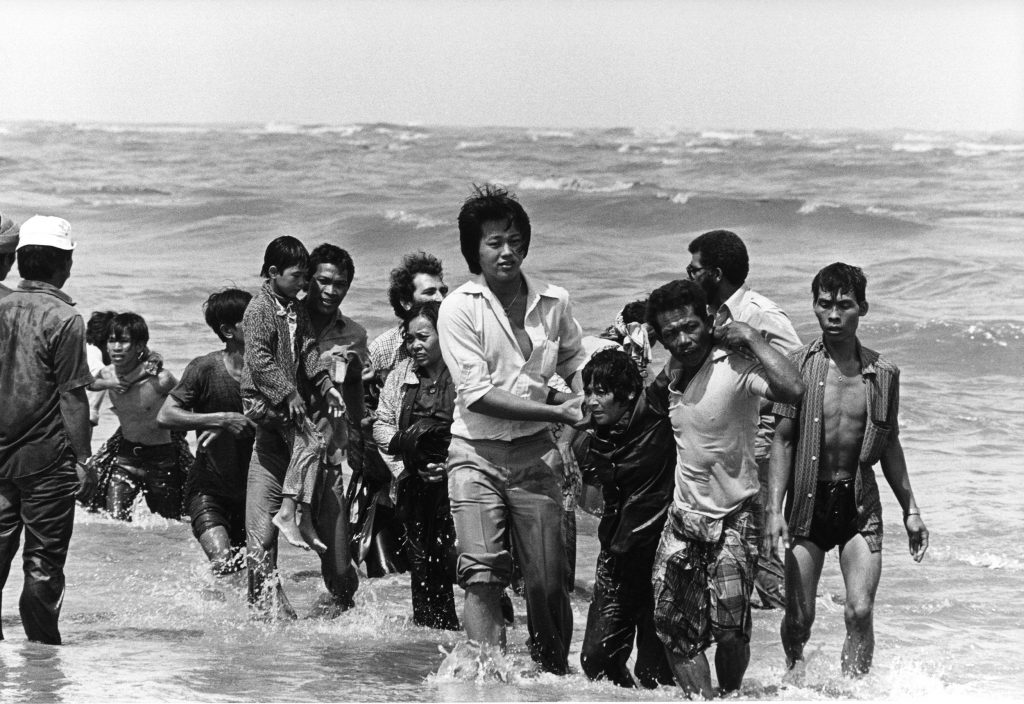

A picture taken in the late 1970s shows a group refugees (162 persons) arrived on a small boat which sank a few meters from the shore in Malaysia.

A picture taken in the late 1970s shows a group refugees (162 persons) arrived on a small boat which sank a few meters from the shore in Malaysia.Bidong Island became the primary refugee camp in Malaysia when it was opened in August 1978. With a land mass of just 260 hectares, Bidong was designed for 4,500 refugees, but by June 1979 Bidong had a population of over 40,000.

Bidong Island camp, 1979 (UN)

Bidong Island camp, 1979 (UN)As thousands of mainly southern Vietnamese continued to leave their home country illegally, both the Malaysian and Indonesian governments were criticized by international groups for towing boats back out to sea and pushing them into the other’s waters.

As this very public humanitarian crisis was unfolding, a lesser known group of refugees were quietly arriving in Malaysia, mostly from Cambodia, and mostly Muslim.

This group were known as Muslim Cambodians (Kemboja) or Malay Cambodians (Melayu Kemboja), later becoming referred to as Melayu Champa or Cham Malays.

Unlike the majority of Vietnamese refugees who arrived by boat, the Chams mainly came to Malaysia overland in two distinct groups.

The first originated from among the Cham communities in Vietnam but had travelled to Cambodia before leaving again towards Thailand. Many Chams from the coastal areas in places like Saigon, Phan Rang and Nha Trang moved to border towns such as Chau Doc and Tay Ninh before crossing over to Cambodia as the war in Vietnam intensified. From Thailand they headed south and crossed the border into Malaysia.

The second group came from Cambodia. Known as Cambodian Chams, they consisted of generations who had steadily migrated from Vietnam to areas such as Kampong Cham and areas north of Phnom Penh since the decline of Champa in 1471.

Meanwhile, the Malaysian government faced pressures from welfare organizations such as PERKIM (Pertubuhan Kebajikan Islam Malaysia/Muslim Welfare Organisation of Malaysia) and other political parties to assist the Cham Muslim refugees. The Organisation of Islamic Countries (OIC) also put pressure on Malaysia in the name of Islamic solidarity

Both humanitarianism and a shared religious bond were brought forward as a case for temporary resettlement in what was the closest Islamic majority nation to the new communist regimes.

As early as June 1975, only months after the fall of Phnom Penh, Malaysian embassy officials in Bangkok were working with Thai authorities and UNHCR. They began visiting refugee camps and identifying Chams among the displaced peoples, in order to process applications to relocate them.

Many took up the offer and towards the end of 1975, 1,279 Cham refugees were accepted into Malaysia. The process continued well into the late 1980s, resulting in a total of 9,704.

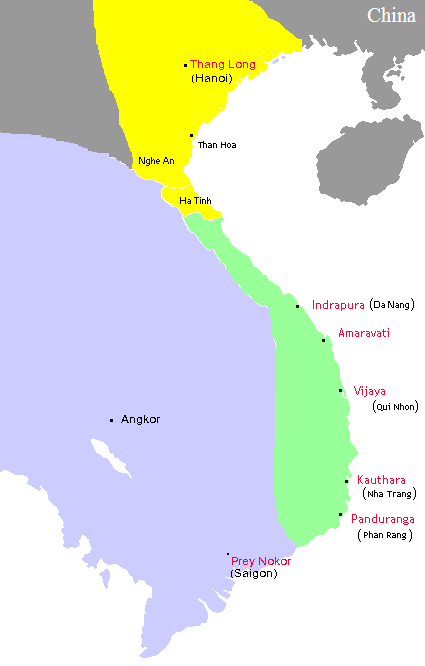

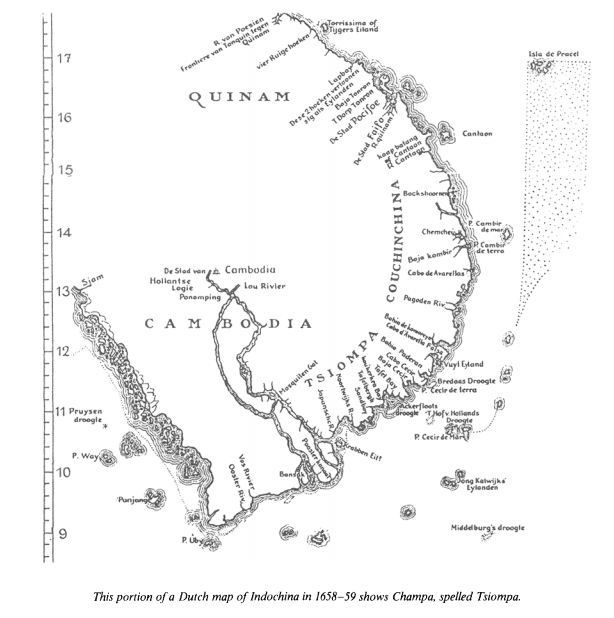

The history of Cham settlement in Malaysia, especially the state of Kelantan, predates the communist wars by 500 years. As, what was then, Kingdom of Dai-Viet began pushing further south, the old kingdom of Champa fell.

Cham warriors in a boat, depicted on the Bayon

Cham warriors in a boat, depicted on the Bayon Champa (green) c1100

Champa (green) c1100

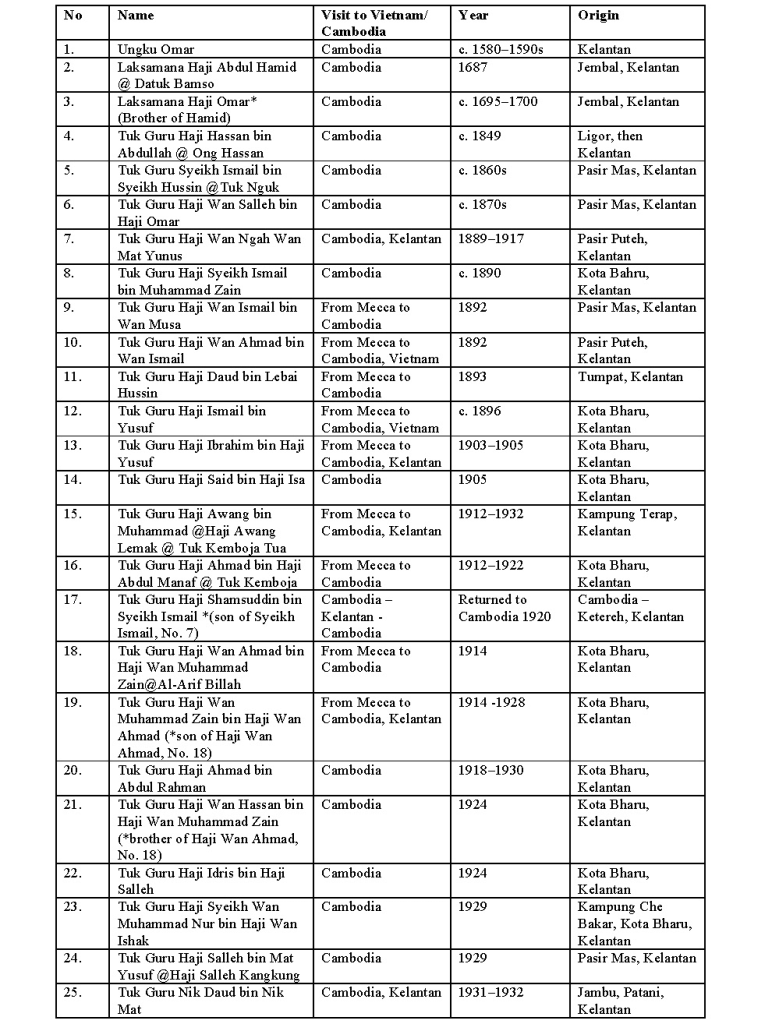

Male missionaries named 1580-1932

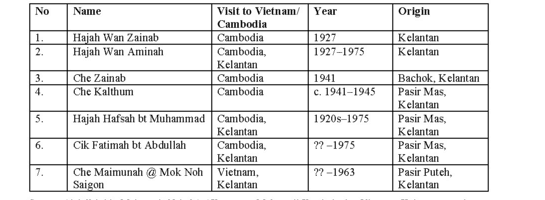

Male missionaries named 1580-1932 Female missionaries named source: Abdullah bin Mohamed (Nakula), “ Keturunan Melayu di Kemboja dan Vietnam”

Female missionaries named source: Abdullah bin Mohamed (Nakula), “ Keturunan Melayu di Kemboja dan Vietnam”